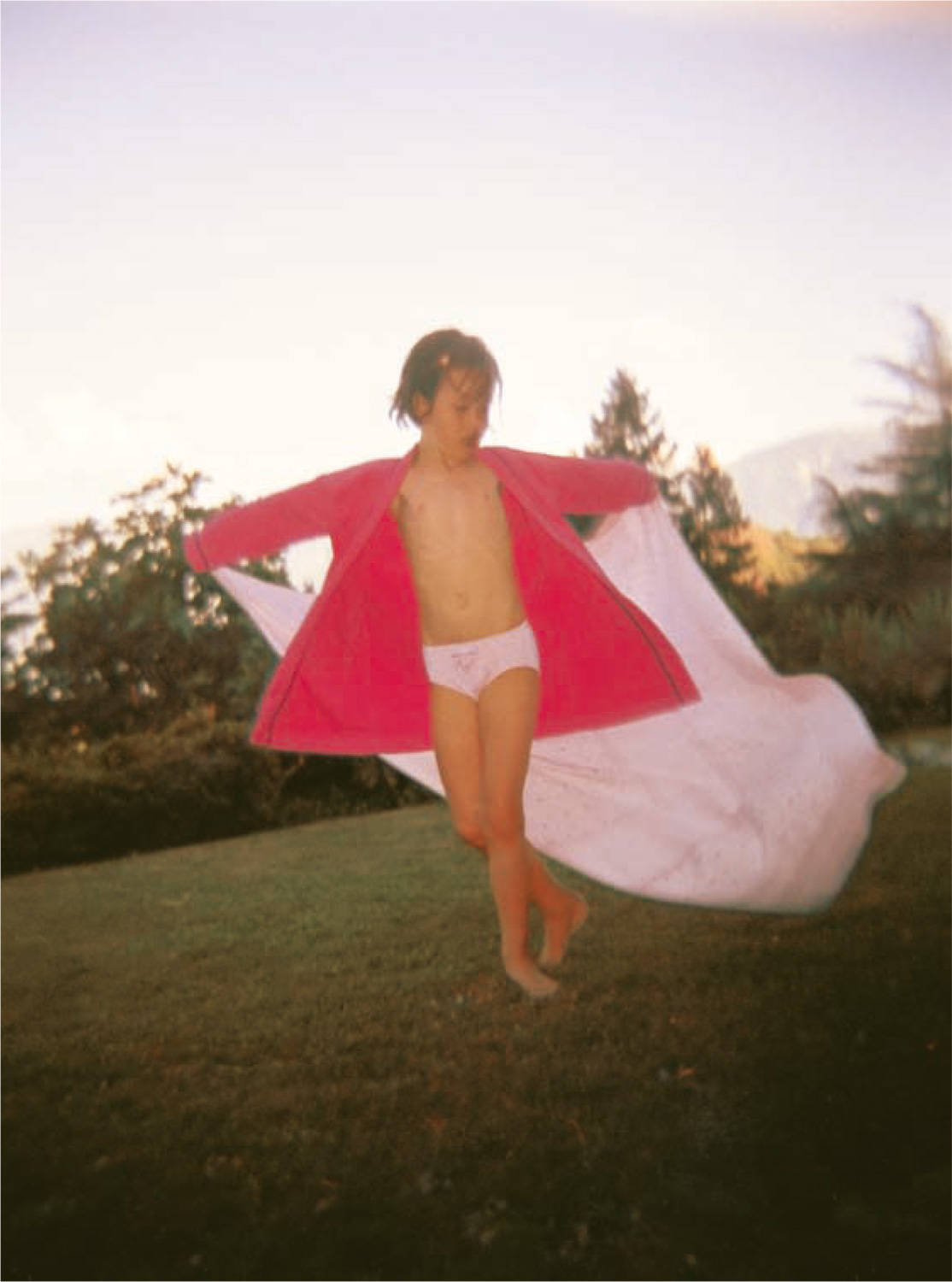

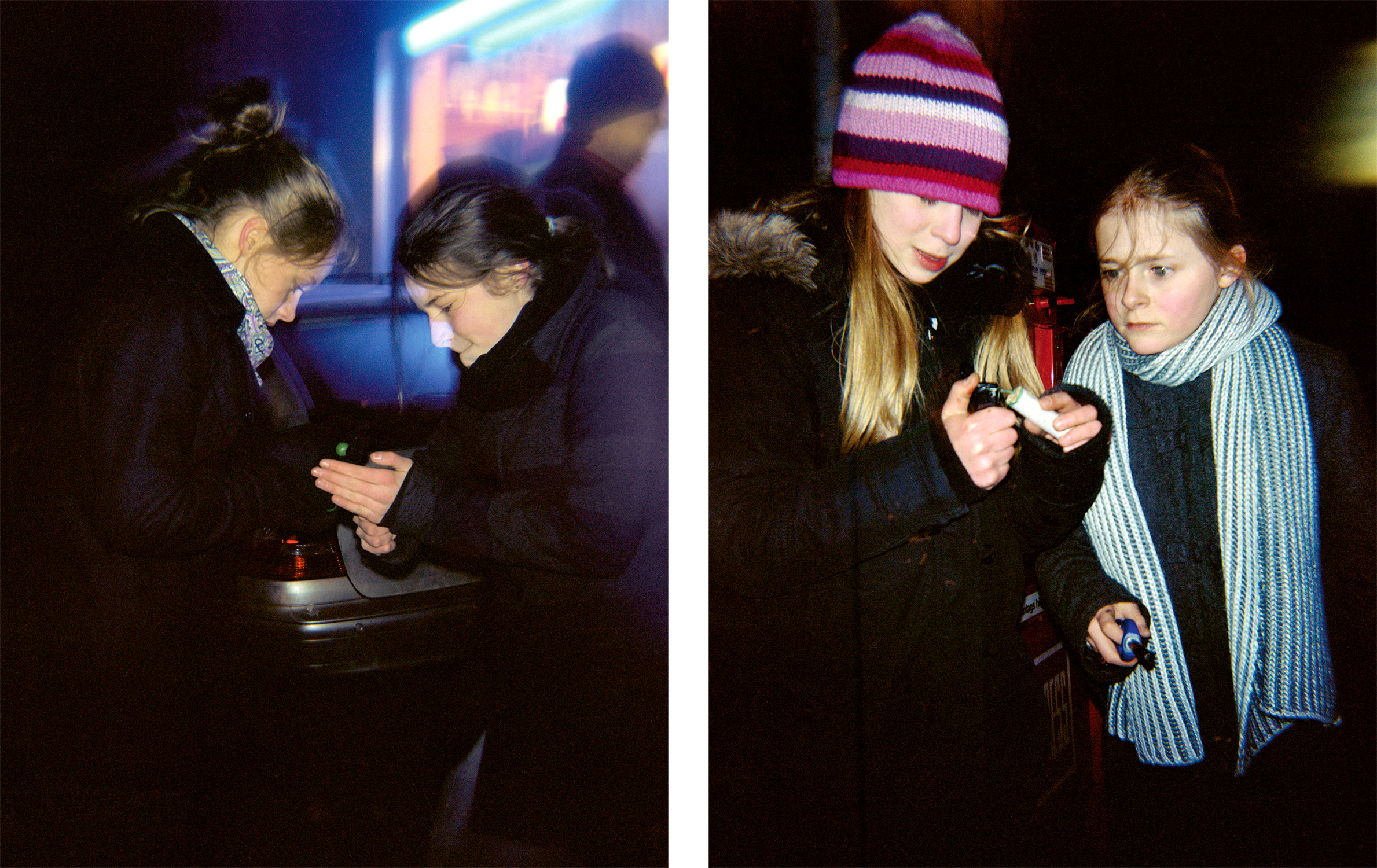

The Last Year of Childhood

Package from Tokyo

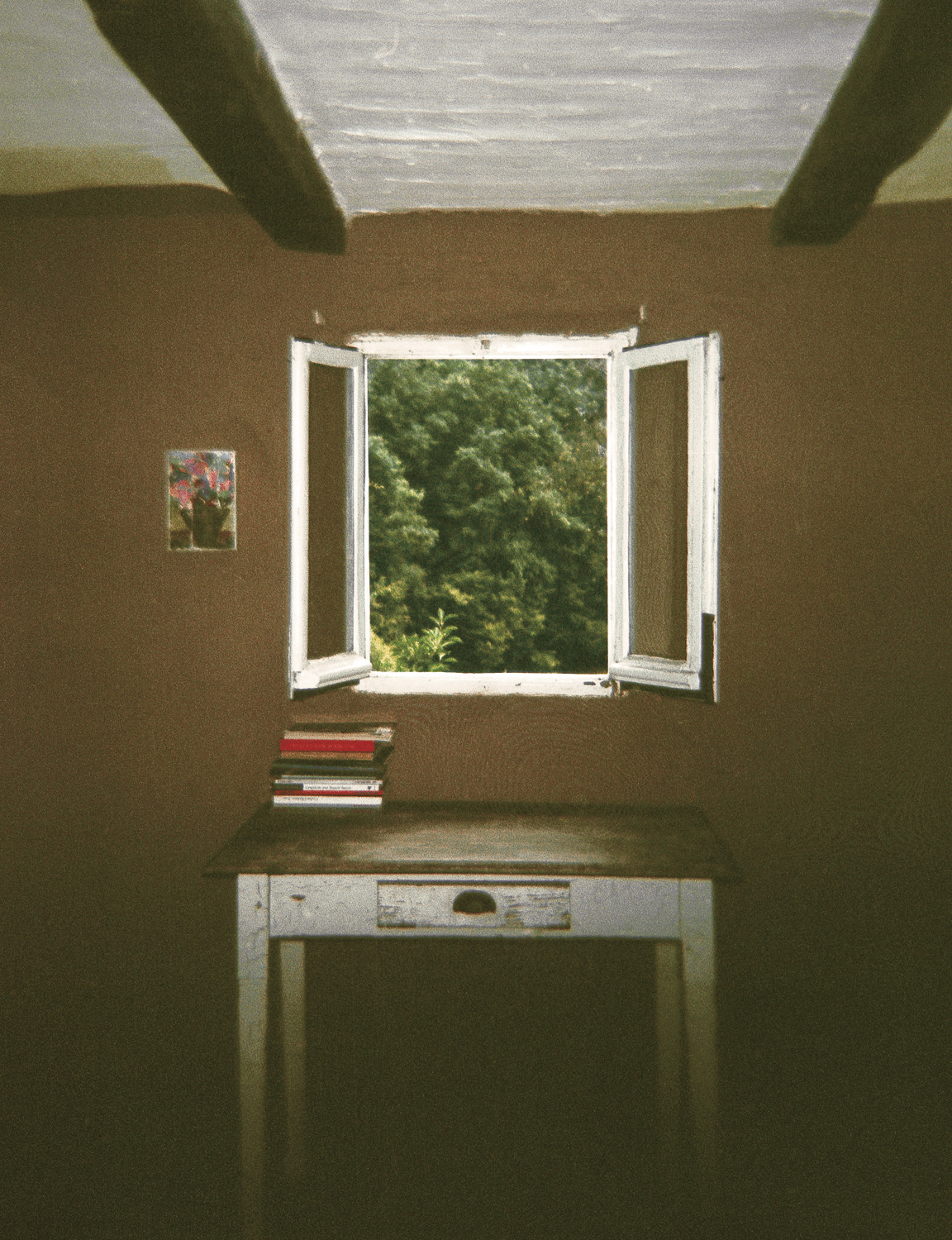

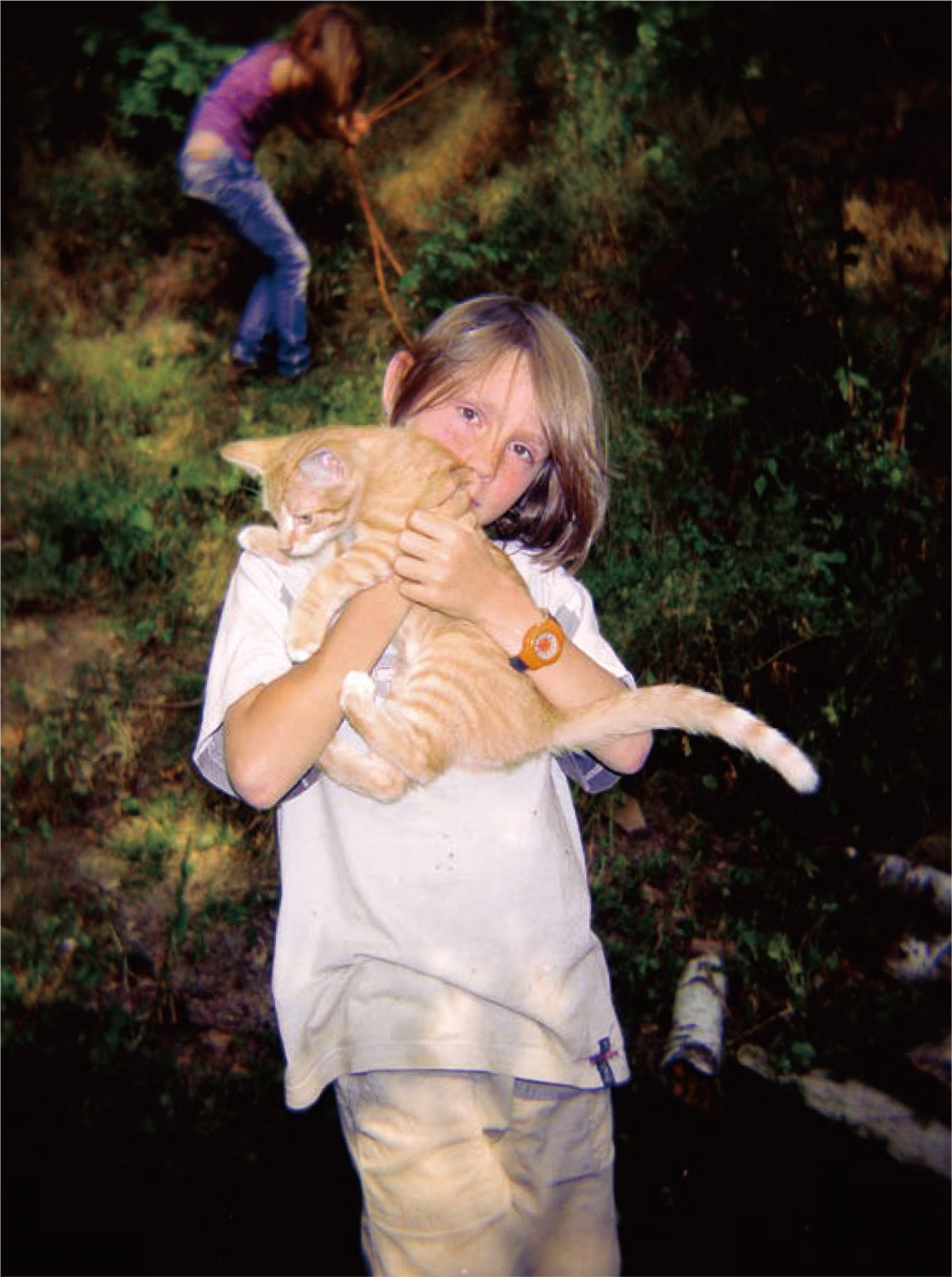

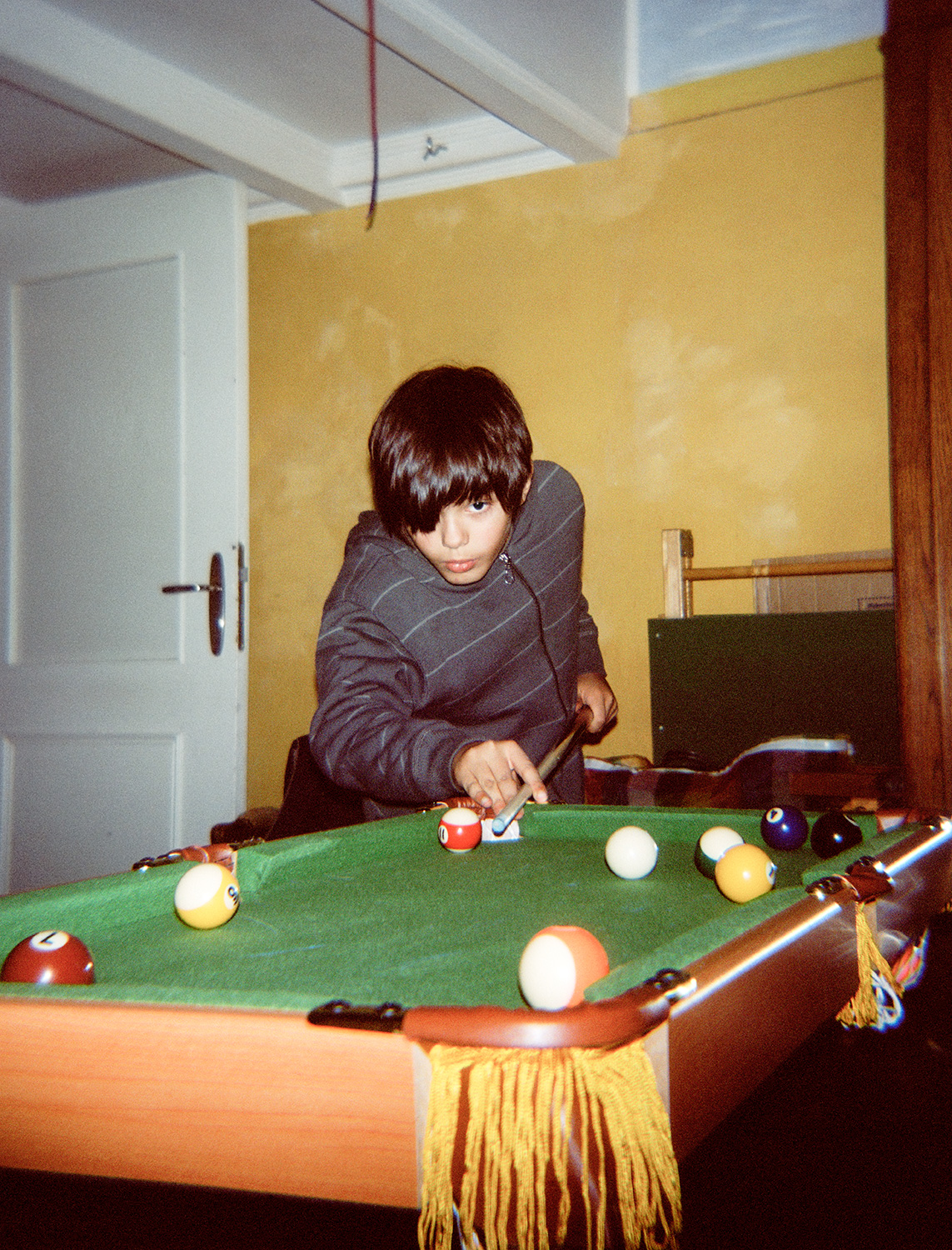

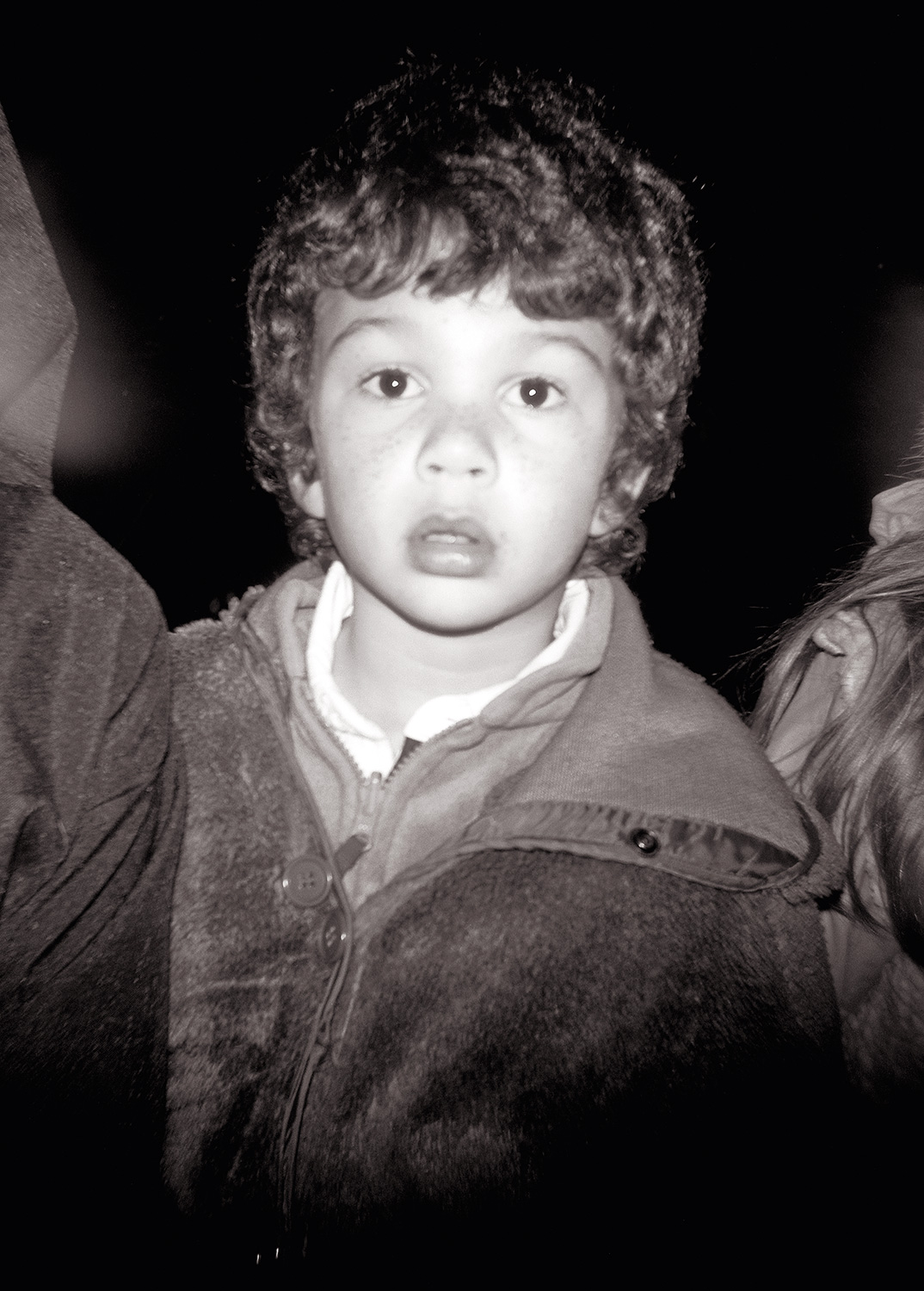

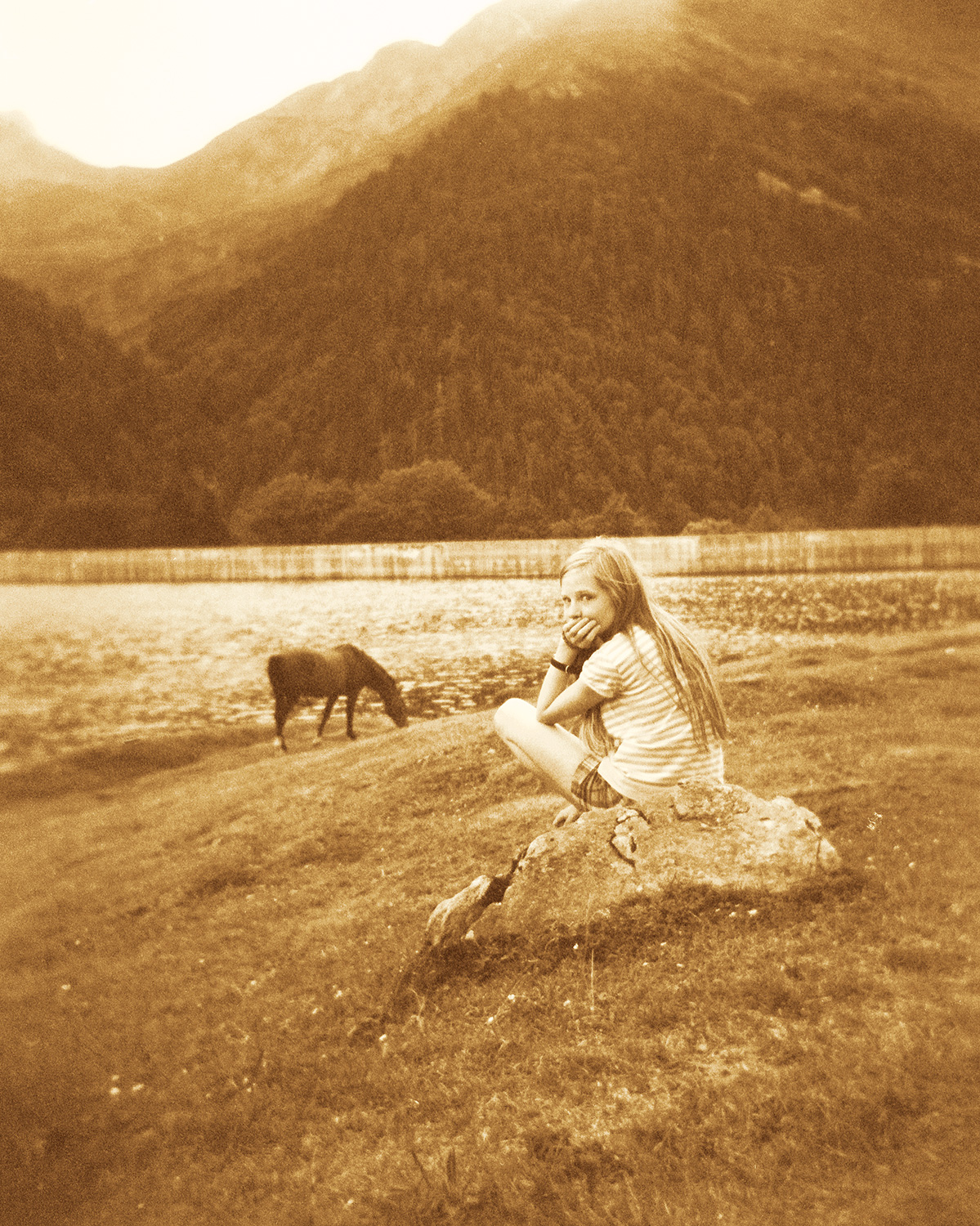

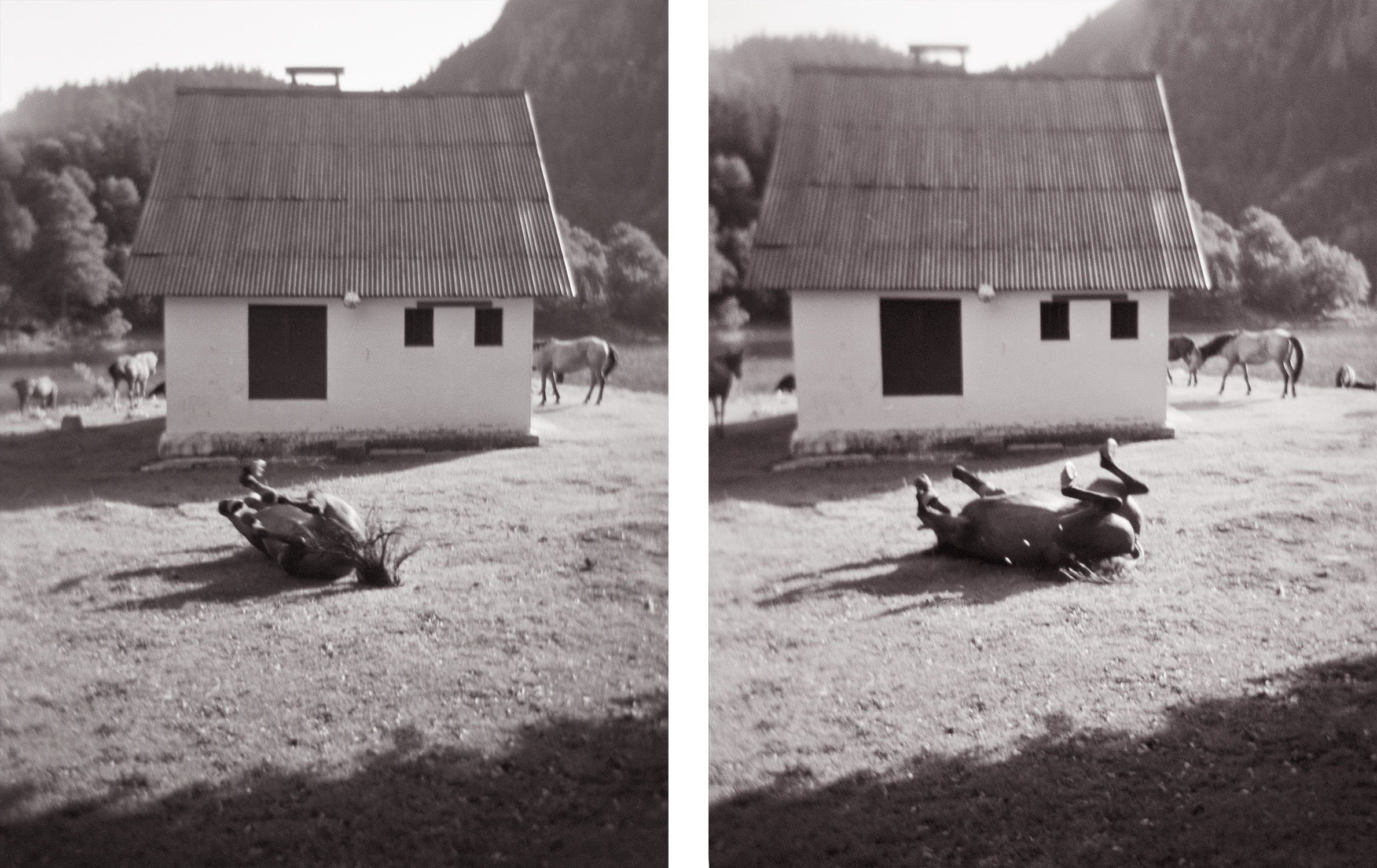

The Last Year of Childhood, the new photo book by Cologne-based artist Ute Behrend, tells of the transition between childhood and adulthood. It brings together images from that mysterious realm between carelessness and strangeness, and is also the product of a Japanese-German collaboration. The Tokyo-based publisher, Powershovel Books, invited Ute Behrend to conduct an experiment in analogue photography. The artist was given the choice of several cheap cameras and opted for the large version of Holga, the former Chinese "people’s camera". It was the beginning of a project lasting many years and culminating with The Last Year of Childhood.

The Holga fulfils the secret desire of many photographers with its proximity to a painterly aesthetic. Technical deficiencies reminiscent of old photographs, such as blurring and the vignetting, are characteristic for the Holga. The admittedly limited coincidental look the camera produces gives the images a nostalgic glaze that seems to correspond with the emotional subject way too much. But Ute Behrend seems to know how to tame it and employs its technical possibilities with virtuosity, without lapsing into sentimentality. The main priority for her is telling people’s narratives.

The people observed thus in their "narratives" move through time and space. But there is also a third movement: that of the narrative images themselves. Time and again they suggest new possibilities for thinking about perception, contact, solitude and community, intimacy and masking. They pull in a new level of responses to the people and their environment: they reflect that our consciousness itself, whether that of a child or an adult, is little more than a rather inaccurate camera that we always have to carry around with us. Ute Behrend presents not only a dreamy story about the loss of childhood, but also a hyper-alert essay on photography itself.

Christoph Ribbat

-

Kunstmuseum Mühlheim an der Ruhr, 2018 -

Kunstmuseum Mühlheim an der Ruhr, 2018 -

PARIS PHOTO, 2013